Poka-Yoke & the Planning Fallacy

Most startups hate planning. Poka-yoke and how to do it right.

November 2025

Most startups hate planning. Or rather, most founders do. When I hear a founder say “planning,” they say it the way people say “dentist.” Their voice slows and their limbs slacken as they succumb slightly more to gravity.

Here are some some things I've heard:

“By definition, future plans are wrong.”

“All plans are artificial precision.”

“Don’t do work about the work. Just do the work.”

“Planning is a waste of time.”

There’s some truth to these, because most planning processes fail when startups are learning to do them. The good news is that they fail for predictable and avoidable reasons. And startups should want to get this right, because planning is a form of coordination, and startups can’t scale without some coordination.

The Bad Ways

How coordination happens matters a lot. In many startups, it happens badly.

The first predictable failure mode is drag. This happens when each individual coordination point is too complicated: too many people (20-person ZoomsNever better depicted than here.), too many review loops, unmanaged long meetings, or talking around real issues.

Dogmatic adherence to structure is another failure mode. A few I’ve lived through include esoteric plan structures, forced themes or groupings, and grammar strictures. In one planning process certain verbs were allowed and others weren’t. If structure and form usurp usefulness, coordination fails.

The third common failure mode is participation trophy planning, where every team gets every activity recognized. Effective planning is prioritization, where teams decide what needs to happen, and what doesn’t. I spoke with one COO who was hired into a company of less than forty people then found out they had 160 OKRs. I imagine there was a significant participation trophy culture at that startup at that time.This COO redid the planning structure and culture at that startup, and that company brings in >$100M in revenue now. It’s not effective.

One friend of mine called them “success theater,” which is exactly what they are. Obviously, I don’t advocate for those. But some planning and coordination is necessary to build and grow a startup.

The Planning Fallacy

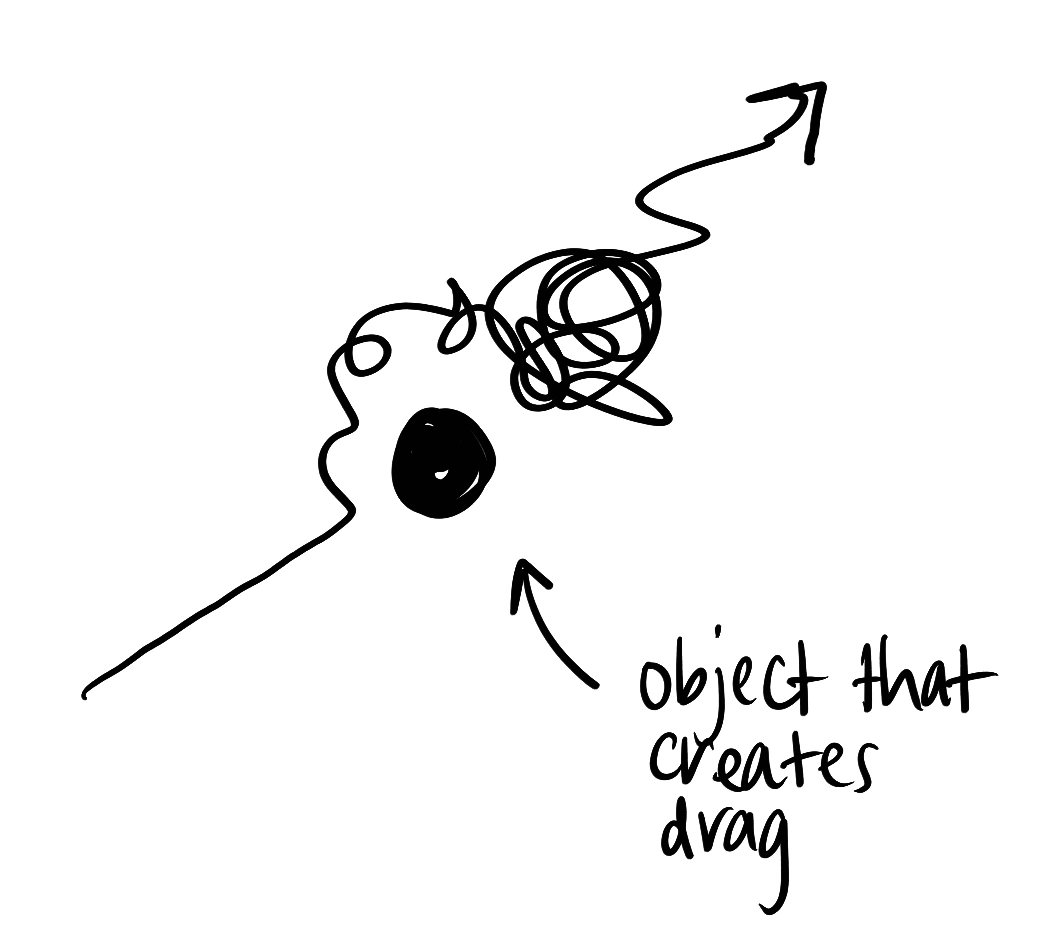

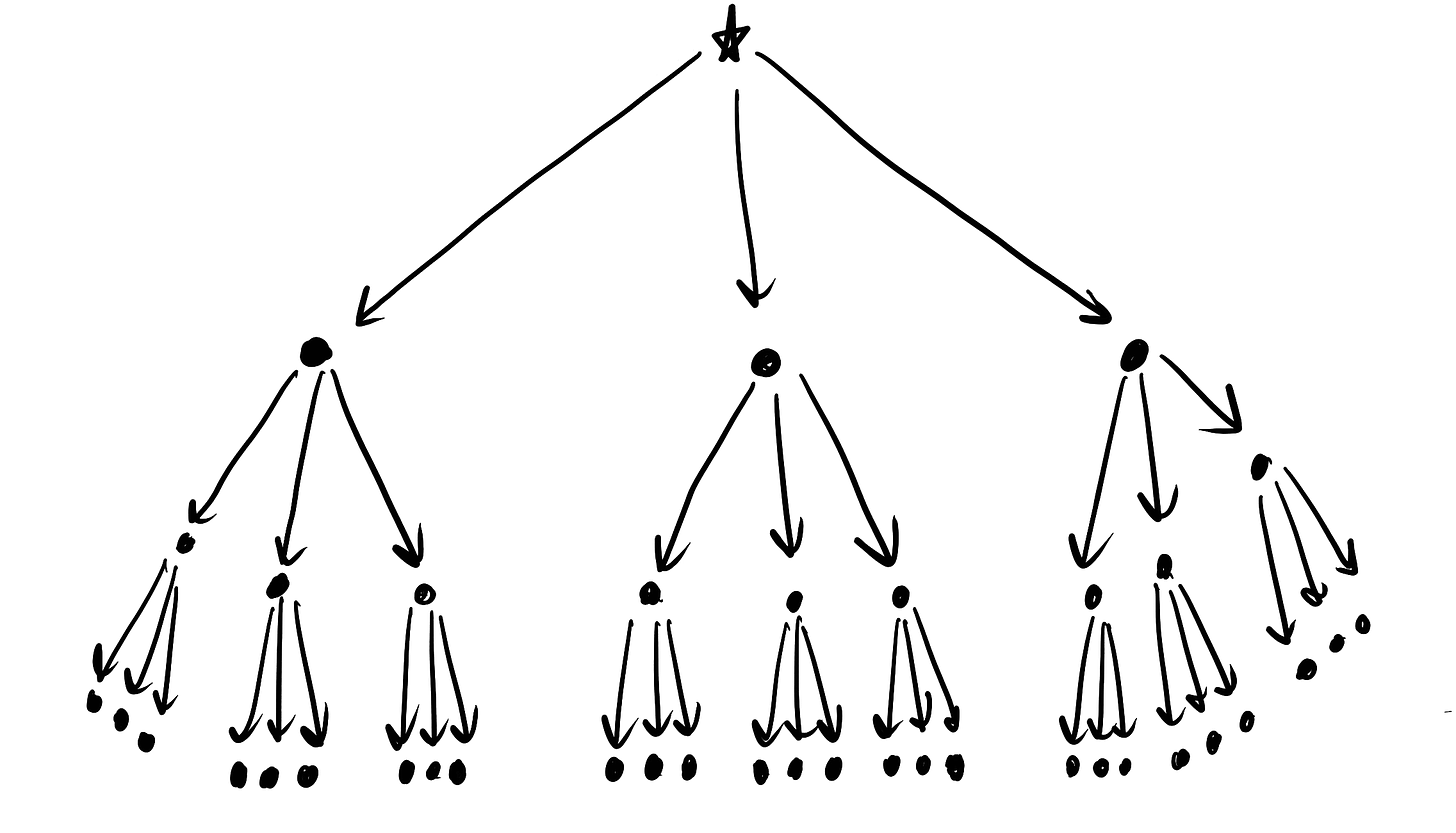

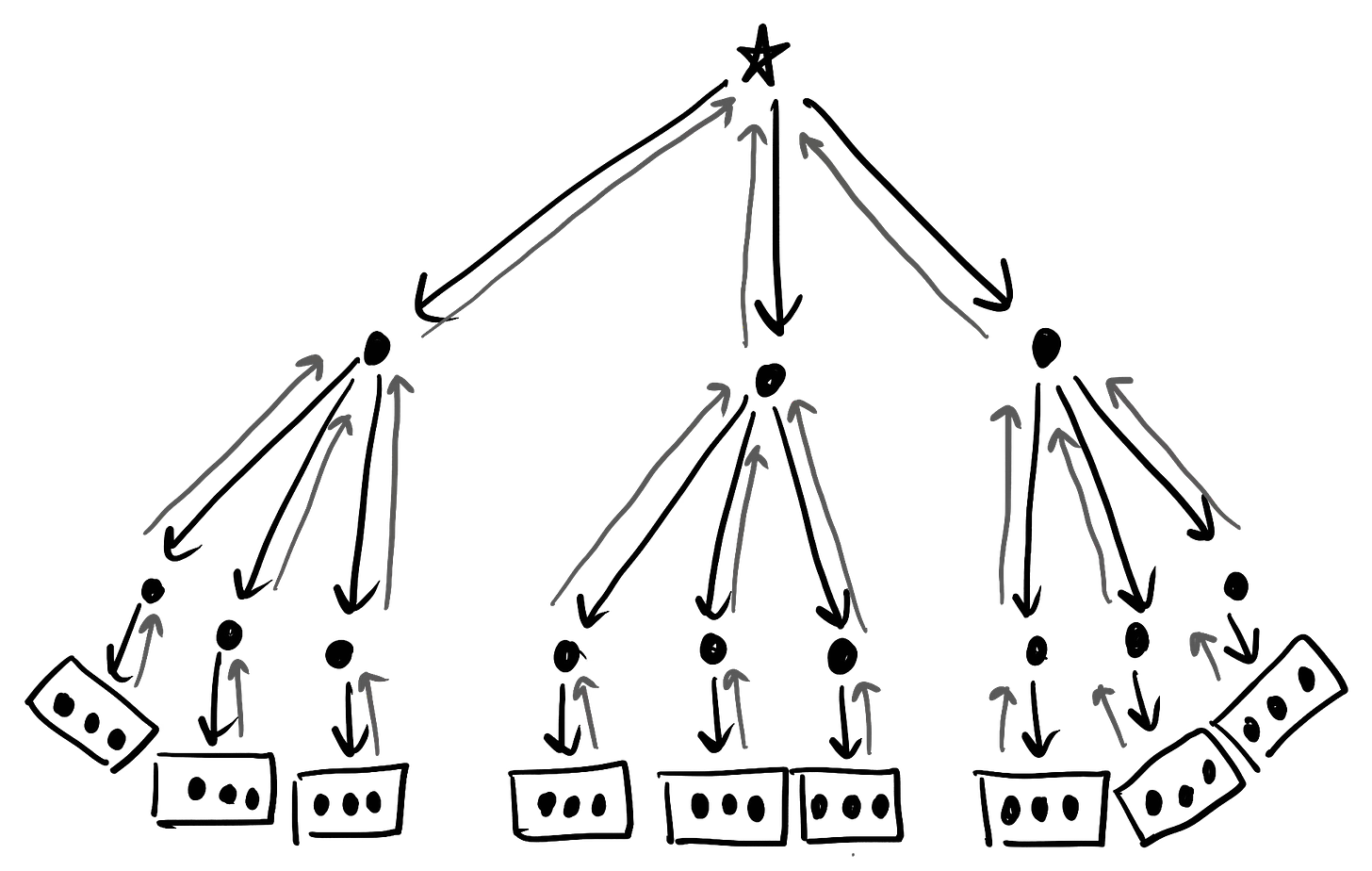

Coordination in companies has been written about for a long time.The earliest source I could find is “The Nature of the Firm” by RH Coase from 1937. This is the paper. The section that’s relevant starts with “first, as a firm gets larger, there may be decreasing returns to the entrepreneur function, that is, the costs of organising additional transactions within the firm may rise.” To illustrate it: imagine a 40-person startup where planning happens in a relatively simple way: 100% top down, where every single person at every level has three direct reports. You could visualize their planning process this way, where each arrow is a coordination point:

That’s a start. But it’s wrong, of course. At the lowest level, managers will bring their teams together for a group discussion. So the number of coordination “arrows” is more likely:

But then, planning isn’t (usually) one hundred percent top down. There is a loop where priorities are also set bottoms up.The best description of this loop is the W-shaped planning process, as described by my Nels Gilbreth and Lenny Rachitsky. So that could be visualized this way.

I think when a founder sees that they think: holy smokes, that’s a lot of arrows. (It’s 42.)

The fallacy is comparing this against no planning. This is how they want it to work, or maybe how it used to work. No coordination! Look at all that free time.

![inline: [small] magic! illustration magic! illustration](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!N9ng!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F22dae1d3-0250-436b-8465-4277cd579beb_1138x1078.png)

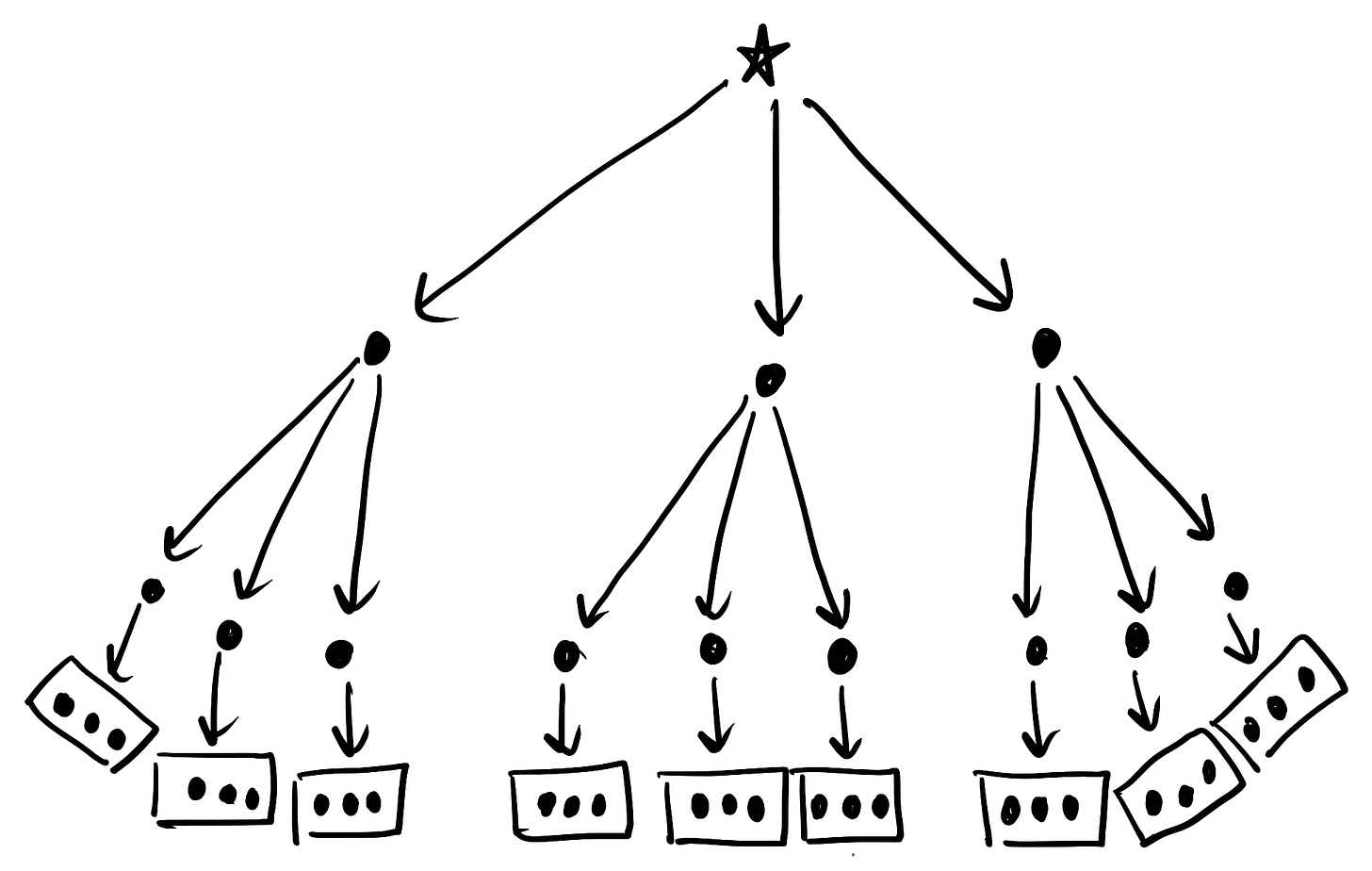

But you can’t build a startup without some level of coordination. How does any one person work on the right thing? So without some kind of planning process, employees coordinate without a system. Which means they all coordinate with each other.A K40 network is beyond my drawing skills. This and the next network drawing are courtesy of ChatGPT.

![inline: [small] k40 network illustration k40 network illustration](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!C3eS!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fdf11fbae-c3eb-489f-9510-a3db9df351b7_1456x1419.png)

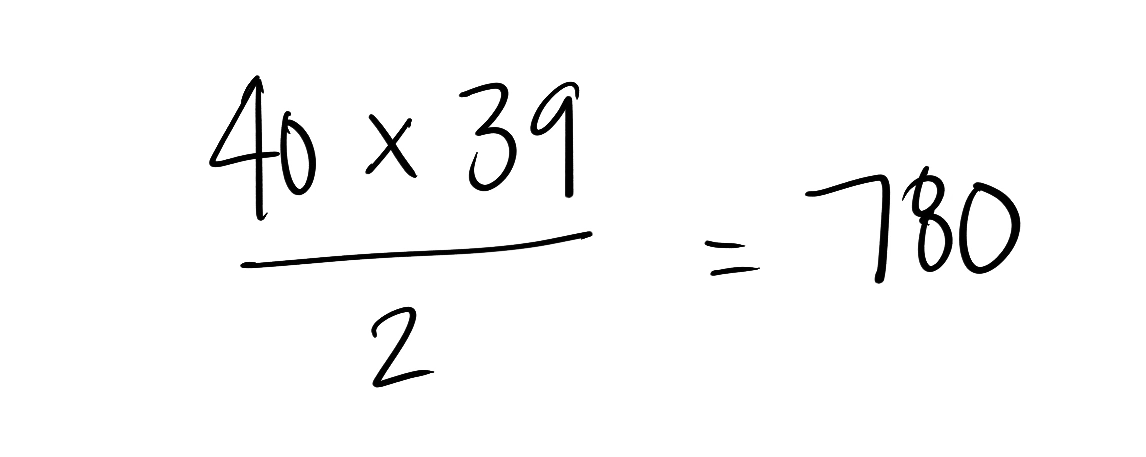

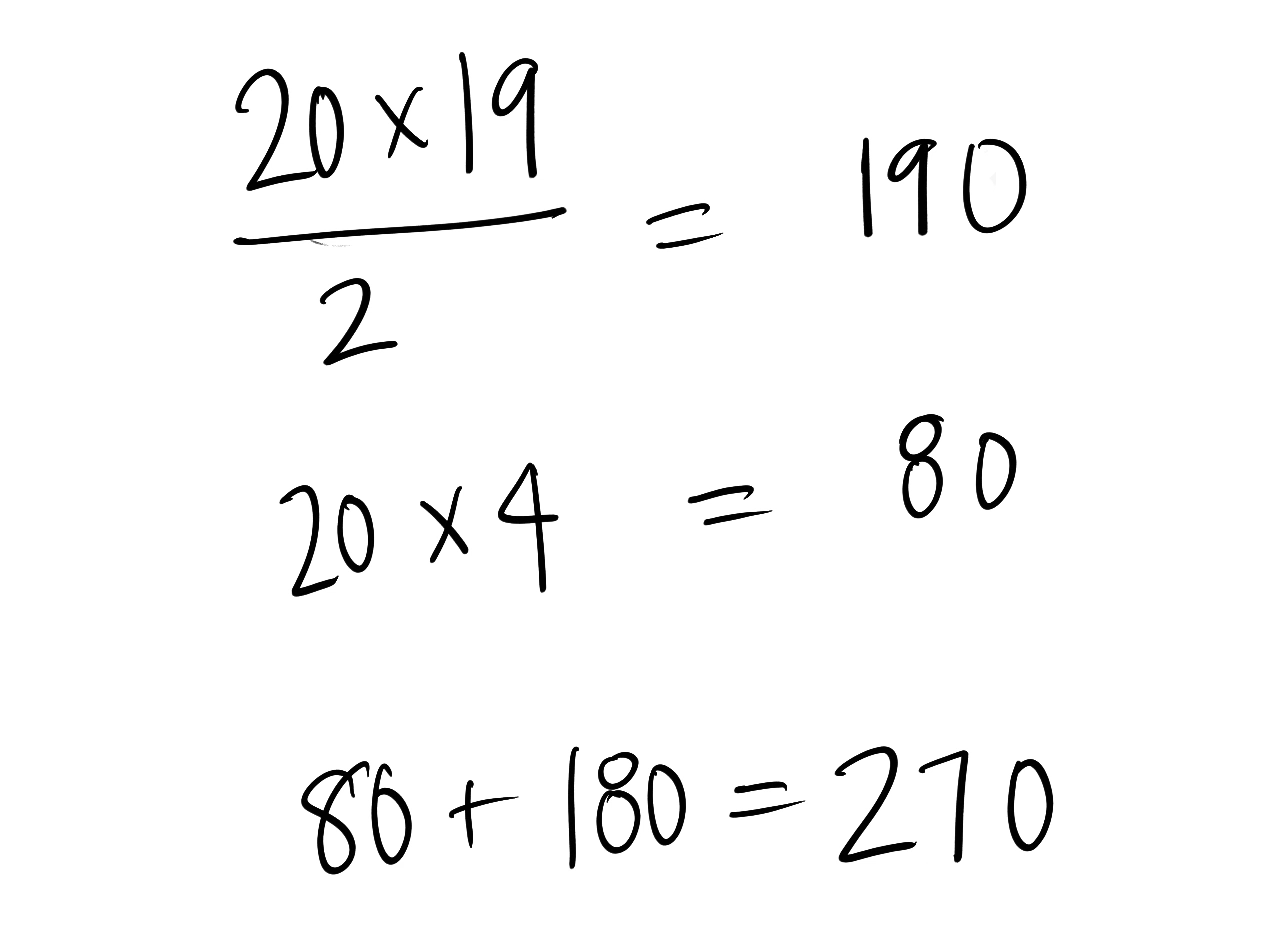

The most striking thing about this is that the number of arrows is much higher. For a 40-person startup, it’s 780:

For some reason founders often think they are choosing between zero and 42, instead of 42 and 780. This is the planning fallacy.

There are more accurate representations of a company as a network, where some teams are fringe and some are core, and the total number of arrows (in network terms, edges) comes down. But even if half are fringe and set into teams of four, the number of arrows is 270. That’s still a lot more than 42.

There are two consequences of the planning fallacy. The first is simple: 780, or 270, is a lot more than 42. That means moving slower.

The pernicious problem is that there is a negative feedback loop between the planning fallacy and believing planning is bad. The more a founder pushes for zero coordination, the more the planning fallacy takes over, and things become chaotic. And then, the more a founder may end up with the wrongly held view that their push for zero coordination is working.

The Good Ways

Alignment does not have to equal drag. I think the right model is actually poka-yoke, a term from the Toyota Production System and means, roughly, a behavior-shaping constraint.Here’s wikipedia’s primer on poka-yoke. The example I like best is labeling boxes on all sides, so no matter how you absentmindedly put them back on shelves, a label will be facing out. Instead of imaging process, imagine designing a system that makes it easier to make the “right” decisions and harder to make the “wrong” ones.

Some useful principles in approaching planning:

Don’t do it too early. Wait until the math of the planning fallacy means it’s time to centralize coordination, then implement planning the right way.

First, set top-down direction. This prevents burning cycles on areas the company won’t pursue.

Then, limit the number of priorities or plans each team can have. Reward focus and alignment to the top direction, and be explicit about non-goals. Don’t be great at things that don’t matter, which means you have to be clear and in some cases, do the sensitivity analyses.

Acknowledge that this work is an ask. Map onto existing pivot points and remove work where possible. Run cadences according to real life and use hard constraints.For example, don’t ask teams to submit work ahead of time. Just do heads down reading in the meeting. Multiple COOs complained to me “if only people would follow the process I laid out for them, then planning would be easier!” To me, that means the process is badly planned. Poka-yoke means planning for real life.

Ruthlessly weed out participation trophy behavior. Communicate clearly that plans are not performance reviews, not everyone’s work will be recognized, and that’s how it’s supposed to be.

Don’t overrotate on form. Accept activity-based goals at junior levels, and even mid levels if necessary. However, do not flex on this: achievement of a goal or plan should always be objective.

Remember that measurement doesn’t come for free. Align resources (Eng, Data, Analytics, etc) OR change the objective measure/metric to be measurable today, not tomorrow.

Time-box steps to a few days each. Design a process that does not eat up more than 25% of any individual’s time during that period, and less for most employees.

Ask that teams check with each other about dependencies and work it out on their own. Checking with each other should be quick Slacks or A K40 network is beyond my drawing skills. This and the next network drawing are courtesy of ChatGPT. minute phone calls, not big meetings. In cases where dependencies can’t be worked out, give a clear method of how, when, and who to bring that to. And when they bring it, decide and respond quickly (1-This COO redid the planning structure and culture at that startup, and that company brings in >$100M in revenue now. days).

The most important thing is to do all of this in the open. Renouncing planning doesn’t remove coordination, it pushes it into more meetings, secrets, and even sprezzatura. Run a simple, explicit process instead.

Impacts

If you do all this, a light planning process can have meaningful impact in both growth and speed of company operations. Here are a few I’ve observed or heard in my interviews: faster resolution of trade-offs, fewer re-litigated decisions, reduced need for exec arbitration, clarified internal and external company narrative, easier cross-functional collaboration (less thrash), improved accuracy of forecast, reduced spend on initiatives that don’t drive revenue. Who wouldn’t want all that?

Thanks to CR, Chris, Perry, Julie, Rob, Ami, and Dimitri for reading drafts of this essay. And thanks to Sanjay for teaching me about poka-yoke.